Comparative Analysis of Malaria Vector Sporozoite Load and Malaria Prevalence Among Vulnerable Populations in Wukari, Taraba, Nigeria

| Received 25 Sep, 2025 |

Accepted 14 Jan, 2026 |

Published 15 Jan, 2026 |

Malaria continues to be a major public health challenge in Sub-Saharan Africa, where transmission is shaped by the interplay of vector ecology, human behavior and health system limitations. This study investigated malaria transmission dynamics in Wukari Local Government Area of Taraba State, Nigeria, by integrating entomological surveillance with epidemiological assessments among vulnerable populations. Over a twelve-month period, adult Anopheles mosquitoes were collected using standardized trapping methods, identified morphologically and by PCR and examined for Plasmodium sporozoites. Concurrently, cross-sectional surveys were conducted among febrile children aged 0-5 years and pregnant women to determine malaria prevalence using rapid diagnostic tests and microscopy, while also documenting preventive practices and healthcare access. A total of 450 female Anopheles mosquitoes were analyzed, with sporozoites detected in both midguts (65.8%) and salivary glands (34.2%), confirming high transmission potential. Weekly infection intensities showed no significant fluctuations, but spatial heterogeneity revealed localized hotspots of residual transmission. Among human participants (n = 156), malaria prevalence was highest in children under five, who accounted for nearly three-quarters of infections, while pregnant women, particularly those aged 18-34 years, also showed considerable vulnerability. The disparity in prevalence between groups was statistically significant (χ2 = 27.115, p = 0.001). Healthcare infrastructure assessments highlighted uneven diagnostic and treatment capacity, with larger hospitals better equipped than smaller facilities that suffered from shortages of personnel and laboratory resources. These systemic gaps, combined with limited coverage and inconsistent use of insecticide-treated nets and antenatal preventive measures, contributed to sustained transmission. The findings underscore the urgent need for geographically targeted interventions, including strengthened vector control, improved antenatal chemoprevention and expanded access to sensitive diagnostic tools. Investments in local laboratory capacity, routine entomological monitoring and community engagement are essential to enhance uptake of preventive measures and adapt strategies to evolving transmission patterns. By linking entomological and epidemiological data, this study provides an actionable evidence base for optimizing malaria control in Wukari and similar high-burden settings, with the ultimate goal of reducing morbidity and moving toward elimination.

| Copyright © 2026 Egwu et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

INTRODUCTION

Malaria remains a leading global public-health threat, responsible for hundreds of millions of infections and substantial mortality worldwide1. Although international efforts have reduced burden in some regions, the disease persists where vector-human-environment interactions, health-system limitations and socioeconomic vulnerabilities converge to sustain transmission2. In Nigeria, national averages conceal sharp within-country heterogeneity: spatially explicit analyses and geostatistical models identify high-burden pockets that concentrate risk and demand locally tailored responses3. Local community surveys and facility-based studies likewise report persistently high parasite prevalence, including large reservoirs of asymptomatic infection among children, underscoring the difficulty of interrupting transmission in many endemic settings4,5.

Vector control remains the foundation of malaria prevention. Widespread distribution and correct use of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) and targeted indoor residual spraying (IRS) where appropriate, have demonstrable protective effects and are central to programmatic strategies6. At the same time, biomedical innovation is altering the prevention landscape: Novel vaccine platforms and the first monoclonal antibody interventions against Plasmodium are advancing through trials and early deployment, offering complementary tools to vector control and chemoprevention7. Parallel improvements in diagnostics from more sensitive rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) to automated and digital microscopy are strengthening case detection, surveillance and the ability to monitor transmission dynamics at finer scales8.

Despite these advances, the effectiveness of current tools is threatened by evolving biological and operational challenges. Antimalarial drug resistance and increasing insecticide resistance among vector populations demand continuous surveillance and adaptive programmatic responses9. Moreover, the persistence of malaria hotspots is shaped as much by social and environmental determinants as by biology: Household living conditions, water and sanitation, access to preventive tools and health-seeking behaviors all interact to produce micro-epidemiological variation in risk10. Consequently, interventions that succeed at the national scale often need local adaptation informed by granular data on transmission, health-system capacity and community practices11.

These realities argue for integrated, evidence-driven approaches that combine strengthened diagnostics, targeted vector control, appropriate chemoprevention and vaccination strategies and investments in health-system capacity12. Programmatic decisions should be guided by locally derived entomological and epidemiological data so that resources are directed to the populations and places most at risk12. Such an integrated framework supports both immediate morbidity reduction and longer-term moves toward transmission interruption by aligning interventions with the ecological and social determinants that sustain malaria locally12.

In this study, an integrated approach is applied to a high-burden locality in North Central Nigeria. Entomological surveillance of local Anopheles populations was combined with cross-sectional epidemiological assessment among two vulnerable human groups, children aged (0-5) years and pregnant women, to quantify vector infectivity (Plasmodium sporozoite rates) and to relate these measures to human parasite prevalence12. By situating entomological and clinical observations within local climatic patterns and by considering the practical implications for chemoprevention, emerging vaccination strategies and diagnostic and surveillance capacity, this study aims to provide an actionable evidence base for targeted malaria control in Wukari LGA, Taraba State12.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

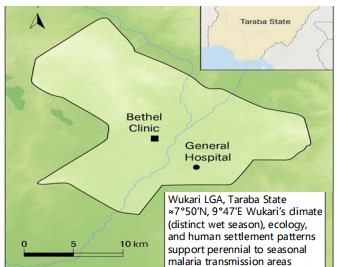

Study area: The study was conducted in Wukari Local Government Area, Taraba State, Nigeria (approximately 7°50 N, 9°47 E). Field work took place over twelve months, from October, 2022 to March, 2023. Monthly entomological surveys were undertaken across selected communities to capture seasonal

|

Shaded relief and contour lines show relative elevation across Wukari LGA (synthetic relief for contextual visualization). Blue lines: Streams/rivers, Green shaded patches: Vegetation, Black square: Bethel clinic, Black circle: General Hospital, Inset shows Taraba State within Nigeria, scale bar and North arrow included-map is schematic for study context (not a navigational chart)

trends. In addition, an intensified entomological trapping module ran weekly for nineteen consecutive weeks within the overall study period to provide higher resolution vector data and capture short-term fluctuations13. The wet and dry seasonal climate, local ecology and settlement patterns in Wukari support perennial to seasonal malaria transmission; these factors guided the sampling frame and site selection14.

Figure 1 shows the Wukari LGA boundary with shaded relief and contouring to indicate relative terrain, major streams and vegetation patches across the study area.

Bethel Clinic (black square) and General Hospital (black circle) are marked; the inset map locates Taraba State within Nigeria and the map includes a North arrow and 0-10 km scale bar.

Approximate coordinates are given (≈7°50 N, 9°47 E) and a short note links the area’s distinct wet-dry season climate and settlement patterns to perennial/seasonal malaria transmission.

Study population and sampling: A stratified random sampling approach was employed to select three wards along with their respective health facilities. Febrile children aged 0 to 5 years and pregnant women presenting with symptoms suggestive of malaria were recruited after obtaining informed consent. The sampling and recruitment strategy was designed to generate reliable prevalence estimates for the target groups and to enable meaningful correlation with entomological data.

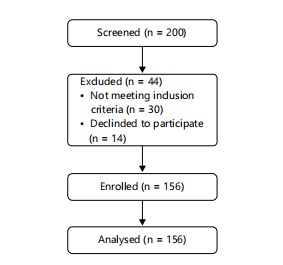

Sample size determination: The determination of sample size was guided by standard epidemiological formulas to ensure sufficient precision for prevalence estimates and valid group comparisons. A total of 156 participants were included, meeting the required statistical power and margin of error necessary to achieve the study objectives.

Figure 2 is a participant flow diagram showing screening (n = 200), exclusions (n = 44: 30 not meeting inclusion criteria, 14 declined) and an enrolled/analysed sample of n = 156.

The diagram directly links to eligibility and recruitment procedures and sample-size determination and analytic denominator, showing how screening and exclusions produced the final study cohort.

|

Participant flow diagram displaying numbers screened (n = 200), exclusions (n = 44: 30 not meeting inclusion criteria; 14 declined), enrolled (n = 156) and analysed (n = 156). n: Number, Excluded: Removed before enrolment, Declined: Refused participation, values are absolute counts that determine the analytic denominator referenced in Sections 2.2 (eligibility/recruitment) and 2.3 (sample-size determination)

The exclusion reasons and counts in the Fig. 1 correspond to the screening/enrolment steps described in those Methods sections, supporting transparency of the analytic sample.

Diagnostic procedures (human): On-site RDTs were performed using WHO-recommended antigen combinations (pHRP2/pLDH) and interpreted per manufacturer and program guidance15,16. To validate field diagnoses, thick and thin blood smears were prepared and read using Giemsa microscopy; slide reading followed harmonized microscopy practices for clinical research and included double-reading for quality control17-19. Given diagnostic innovations, we also referenced studies evaluating automated and digital microscopy approaches to contextualize field methods20,21.

Entomological collection and laboratory procedures: Adult female Anopheles were collected weekly for 19 weeks using standard entomological trapping and aspiration techniques. Dissections examined midguts and salivary glands for Plasmodium sporozoites; midgut oocyst detection and salivary gland sporozoite detection were used to infer recent infection and infectivity, respectively. Entomological analysis considered local surveillance challenges, including insecticide resistance monitoring and temporal (climatic) drivers of transmission22-24.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria and ethics:

| • | Inclusion: Febrile children (0-5 years) and pregnant women able to consent (or with guardian consent) and not recently treated for malaria | |

| • | Exclusion: Severely ill individuals requiring urgent referral or participants who had taken antimalarials/antibiotics in the two weeks prior. The study protocol received ethical approvals from relevant institutional review boards |

Data management and analysis: Data were entered and analyzed using standard statistical software. Descriptive statistics summarized prevalence and entomological indices. Associations were tested using chi-square and logistic regression as appropriate, with p<0.05 considered statistically significant. Data interpretation was guided by regional evidence on climatic influences, household determinants and programmatic responses.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Mosquito sporozoite infection rates: A total of 450 female Anopheles mosquitoes were examined. Sporozoite presence was identified in both the midgut (65.8%) and salivary glands (34.2%), indicating substantial transmission potential (Table 1). Analysis of weekly infection intensities revealed no statistically significant fluctuations throughout the study period (Table 2).

| Table 1: | Midgut and salivary gland sporozoite load of mosquitoes captured during the studies (N = 345) N = number of mosquitoes captured | |||

| Gut Segmen |

No. of mosquitoes examined |

Sporozoite Load +ve |

Sporozoite Load -ve |

Percentage of Sporozoite load (%) |

χ2 | p-value |

| Midgut | 297 | 227 | 70 | 65.8 | 34.44 | 0.00001 |

| Salivary gland | 153 | 118 | 35 | 34.2 | ||

| Total | 450 | 345 | 105 | 100 | ||

| p-value: χ2 = 34.44, p = 0.00001, Midgut and Salivary Gland sporozoite load in captured Anopheles mosquitoes: Lists gut segment, number of mosquitoes examined, sporozoite-positive (+ve) and sporozoite-negative (-ve) counts and sporozoite load (%), N: Total mosquitoes, Sporozoite load: Presence of sporozoites in the specified tissue, values are headcounts and column percentages per gut segment, the reported test statistic and p-value describe the statistical association between midgut and salivary gland infection | ||||||

| Table 2: | Weekly sporozoite load in the mosquito population studied (19 Weeks) | |||

| Week | Sporozoite Load | Prevalence (%) |

| 1 | 20 | 5.8 |

| 2 | 17 | 4.9 |

| 3 | 22 | 6.4 |

| 4 | 20 | 5.8 |

| 5 | 18 | 5.2 |

| 6 | 25 | 7.3 |

| 7 | 23 | 6.7 |

| 8 | 18 | 5.2 |

| 9 | 22 | 6.4 |

| 10 | 17 | 4.9 |

| 11 | 16 | 4.6 |

| 12 | 14 | 4.1 |

| 13 | 12 | 3.5 |

| 14 | 15 | 4.4 |

| 15 | 17 | 4.9 |

| 16 | 15 | 4.4 |

| 17 | 15 | 4.4 |

| 18 | 18 | 5.2 |

| 19 | 21 | 6.1 |

| 345 | 100% | |

| χ2 | 11.48 | |

| P-value | 0.87 | |

| p-value: χ2 = 11.48, p = 0.87, Sporozoite infection rates among captured Anopheles mosquitoes stratified by the variable shown in the table (e.g., species, site or week): Lists No. examined, sporozoite-positive (+ve) and sporozoite-negative (-ve) counts and sporozoite load (%), N: Total mosquitoes examined, χ2: Chi-square statistic, Sporozoite load: Presence of sporozoites in the indicated tissue, values are headcounts and column percentages per stratum, reported test statistics and p-values indicate the strength/significance of comparisons | ||

| Table 3: | Prevalence of malaria parasite (MP) among children, 0-5 Years | |||

| Week | Total No. examined | Children male | Prevalence (%) | Children female | Prevalence (%) |

| 01-May | 25 | 10 | 40 | 15 | 60 |

| 06-Oct | 33 | 15 | 45.5 | 18 | 54.5 |

| Nov-15 | 31 | 17 | 54.8 | 14 | 45.2 |

| 16-20 | 27 | 14 | 51.9 | 13 | 48.1 |

| 56 | 60 | ||||

| Age-based prevalence of malaria parasite (MP) among children (0-5 yrs): Shows weekly total No. examined and sex-disaggregated counts with % prevalence for Male and Female, MP: Malaria parasite, yrs: Years, values are counts and column percentages per week, Total No. Examined: Denotes the sample size for that week | |||||

|

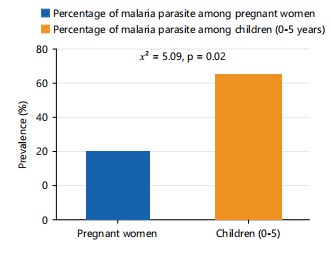

Prevalence (%) of malaria parasite among pregnant women and children (0-5 years). Blue bar: Pregnant women (25.6%) Orange bar: Children, 0-5 years (74.4%), annotations above the bars show χ2 and p-value

Malaria prevalence in children (0-5 years): Children aged 0-5 years exhibited consistently high malaria prevalence. No meaningful differences were observed between male and female participants. Although minor week-to-week variations occurred, this age group remained the most heavily affected overall (Table 3)25-28.

Malaria prevalence in pregnant women: Among pregnant women, infection rates were considerable, with the 18-34 year age group persistently showing higher prevalence compared to women above 34 years (Table 4)29-32.

Healthcare infrastructure and diagnostic capacity: Larger hospitals demonstrated stronger diagnostic capacity, supported by adequate staffing and equipment. In contrast, smaller health centers were constrained by limited personnel and insufficient diagnostic resources, which hindered timely case detection and treatment (Table 5)33,34. Table 5 shows the availability, accessibility and ward capacity of health facilities in Wukari Metropolis. The General Hospital has 5 doctors and 4 wards, while Primary Health Care has no doctors but remains accessible and contains 2 wards. Bethel Hospital has 3 doctors and 3 wards, whereas Waritoma Hospital also lacks a doctor (0 personnel) but has 3 wards. All four facilities are reported to be available and accessible within the study area.

Health personnel availability and staffing composition: Human resource availability varied markedly across facilities. While some hospitals maintained adequate numbers of doctors and nurses, others experienced critical shortages of midwives, laboratory staff and auxiliary workers, negatively impacting malaria case management (Table 6). Table 6 presents the number of health personnel available in Bethel Clinic and the General Hospital. Bethel Clinic has 3 doctors, 2 nurses, 1 midwife, 1 auxiliary nurse, 3 laboratory technicians and 6 cleaners. In comparison, the General Hospital has 6 doctors, 88 nurses, 16 midwives, 100 auxiliary nurses, 15 laboratory technicians and 45 cleaners.

Vulnerability-based malaria prevalence: children (0-5 years) versus pregnant women: Human resource availability varied markedly across facilities. While some hospitals maintained adequate numbers of doctors and nurses, others experienced critical shortages of midwives, laboratory staff and auxiliary workers, negatively impacting malaria case management (Table 7).

Figure 3 is a bar chart showing prevalence (%) of malaria parasite in pregnant women (25.6%) and children (0-5 years) (74.4%).

| Table 4: | Age-based prevalence of malaria parasite (MP) among pregnant women (18-50 years of age) | |||

| Pregnant women | |||||

| Week | Total No. examined | 18-34 (yrs) | Prevalence (%) | 35-50 (yrs) | Prevalence (%) |

| 01-May | 11 | 9 | 81.8 | 2 | 18.2 |

| 06-Oct | 11 | 10 | 90.9 | 1 | 9.1 |

| Nov-15 | 8 | 7 | 87.5 | 1 | 12.5 |

| 16-20 | 10 | 7 | 80 | 2 | 20 |

| 34 | 6 | ||||

| Age-based prevalence of malaria parasite (MP) among pregnant women (18-50 yrs): Shows total no. examined and % prevalence for two age groups (18-34 yrs; 35-50 yrs), MP: Malaria parasite, Values are counts and column percentages per week, Total No. examined: Denotes the sample size for that week | |||||

| Table 5: | Health facilities availability and accessibility and the number of wards in health facilities in wukari metropolis | |||

| Health facilities in Wukari |

No. of health personnel (Dr.) |

Availability and accessibility |

No. wards in health facilities |

| General hospital | 5 | Yes | 4 |

| Primary health care | 0 | Yes | 2 |

| Bethel hospital | 3 | Yes | 3 |

| Waritoma Hospital | 0 | Yes | 3 |

| Health facilities in Wukari Metropolis: lists each facility, the number of medical doctors (Dr.), availability/accessibility status and the number of wards, Wards: Inpatient wards, Yes: Facility available and accessible, Values: “No. of Health personnel (Dr.)” and “No. wards” are counts per facility, “Availability and accessibility” is categorical (Yes/No) | |||

| Table 6: | Health personnel/workers available | |||

| Bethel clinic | Number | General hospital | Number |

| Doctors | 3 | Doctors | 6 |

| Nurses | 2 | Nurses | 88 |

| Mid-wifes | 1 | Mid-wifes | 16 |

| Auxillary nurses | 1 | Auxillary Nurses | 100 |

| Laboratory technician | 3 | Laboratory technician | 15 |

| Cleaners | 6 | Cleaners | 45 |

| Health personnel available by facility: Lists cadres (Doctors, Nurses, Midwives, Auxiliary Nurses, Laboratory Technicians, Cleaners) and their headcounts for bethel clinic and general hospital, Values represent counts (headcounts) per cadre per facility, “Number” denotes the total staff in each category | |||

| Table 7: | Vulnerability-based prevalence of malaria parasite (mp) from population studied | |||

| Vulnerable group | No. of +ve | Prevalence (%) | χ2 | p-value |

| Pregnant women | 40 | 25.6 | ||

| Children (0-5) years | 116 | 74.4 | 27.115 | 0.001 |

| Total | 156 | 100 | ||

| χ2= 27.115, p = 0.001, Vulnerability-based prevalence of malaria parasite (MP) by group: lists each vulnerable group, the number positive (No. of +ve), prevalence (%) and the chi-square (χ2) with p-value, MP: Malaria parasite, χ2: Chi-square statistic, p: p-value (significance), values shown are headcounts (No. of +ve), column percentages (Prevalence %) and the statistical test results (χ2 and p) comparing groups | ||||

Data correspond to Table 7 and support the manuscript’s vulnerability-based prevalence results.

Statistical annotation: The χ² = 27.115, p = 0.001, indicating a significant difference between groups.

The results of this study show that malaria transmission remains intense in the study area: Anopheles mosquitoes carried high sporozoite infection rates and infection prevalence was substantial among children under five and among pregnant women, reflecting the global picture reported by the World Health Organization1. Young children continue to carry a disproportionately large share of the burden, consistent with national estimates and field studies in Nigeria2,3. The notably high infection rates among pregnant women, especially those aged 18 to 34 years, align with evidence that pregnancy increases susceptibility to malaria29,30.

We observed clear inequities in diagnostic and treatment capacity across health facilities, with larger hospitals generally better resourced than smaller clinics, a pattern noted in other African settings and known to hinder prompt case management15,16. Routine reliance on microscopy and standard rapid diagnostic tests, while useful, can miss low density infections, a limitation highlighted by recent evaluations of more sensitive tools9,17. These gaps in detection capacity likely contribute to underreporting and delays in treatment, which help sustain transmission.

Our vulnerability analysis showed that children under five bore the heaviest burden, representing nearly three-quarters of cases in this dataset. Comparable high infection rates among young children have been reported in refugee camps and regional surveys, where malnutrition and socioeconomic disadvantage often compound risk25,26. The persistence of high prevalence despite the availability of interventions such as insecticide-treated nets and indoor residual spraying suggests problems with coverage, correct use or declining insecticide effectiveness, issues documented in systematic reviews and surveillance reports5,6,22. Environmental and household level determinants, including poor sanitation and substandard housing, also appear to amplify risk, as shown in community studies across West and Southern Africa11,12,24.

Although the findings highlight a substantial burden, they also point to practical opportunities. Improving diagnostic sensitivity through newer technologies and automated microscopy could increase early detection and enable timelier treatment19,20,33. Expanding preventive packages for example, broader seasonal malaria chemoprevention and careful introduction of recently developed vaccines such as RTS, S and PfSPZ, may offer added protection for high-risk groups, provided roll-out is well planned and resourced7,8,31,32. Ultimately, the impact of these measures will depend on addressing system-level challenges such as workforce shortages and unequal access to care.

This study has limitations. Its facility-based design likely underestimates community prevalence because asymptomatic carriers, who nonetheless contribute to transmission, may not seek care. The cross-sectional snapshot cannot capture seasonal fluctuations in transmission intensity. Importantly, we did not measure insecticide resistance or antimalarial drug resistance in this work, both of which are critical programmatic factors10. Future research should incorporate longitudinal surveillance, combine entomological and molecular methods and evaluate how emerging tools perform in routine program settings. Strengthening community-level surveillance and investing in resilient, equitable health services will be essential to reducing the malaria burden and making progress toward elimination.

CONCLUSION

Malaria transmission in Wukari remains substantial, driven by high vector infectivity and persistent human infection among children and pregnant women. The entomological and epidemiological evidence together highlight clear hotspots where targeted interventions will have the greatest impact. Strengthening routine surveillance, including regular sporozoite monitoring, is essential to detect and respond to local transmission shifts. Improving diagnostic capacity at smaller health centers will reduce delays in treatment and help uncover hidden reservoirs of infection. Expanded access to preventive measures, especially for children under five and pregnant women, should be prioritized and monitored for effective use. Health system investments in laboratory staffing, training and supply chains will support more timely case management and programmatic decision making. Operational research on insecticide and drug resistance in the study area is needed to guide adaptive vector control and treatment policies. Future studies should include community-based sampling and longitudinal designs to capture asymptomatic carriage and seasonal dynamics. Integrating entomological, clinical and social data will improve the design of geographically tailored interventions and community engagement strategies. Sustained, locally led efforts that combine strengthened surveillance, targeted control and focused research offer the best path toward reducing malaria burden in Wukari.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

Integrated entomological and epidemiological surveillance in Wukari LGA uncovered spatially focal and seasonally driven malaria transmission hotspots that sustain residual burden. By linking vector infectivity (sporozoite rates) with human parasite prevalence among children under five and pregnant women, the study provides a clear, locally relevant evidence base for targeted interventions. Findings demonstrate that geographically focused vector control and strengthened antenatal chemoprevention can efficiently reduce transmission where resources are constrained. The work highlights the operational value of routine, locally led entomological monitoring and strengthened peripheral diagnostics for adaptive programmatic decision-making. Investments in basic laboratory capacity, integrated data systems and community engagement emerge as high-yield strategies to translate surveillance into impact. Overall, the study offers practical, evidence-informed recommendations to accelerate malaria control and move high-burden localities toward transmission interruption.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors sincerely thank the study participants and community leaders in Wukari, Taraba State, for their cooperation and support. We are grateful to the healthcare personnel and facility administrators who facilitated data collection and provided valuable insights. Special appreciation goes to the laboratory and field teams for their dedication to rigorous diagnostic and entomological procedures. We also acknowledge the guidance of our institutional ethics committees and the technical input from collaborating researchers. Finally, we extend our thanks to all individuals and organizations whose contributions made this work possible.

REFERENCES

- WHO, 2023. World Malaria Report 2023. WHO, ISBN: 978-92-4-008617-3, Pages: 356.

- Onyiri, N., 2015. Estimating malaria burden in Nigeria: A geostatistical modelling approach. Geospat Health, 10.

- Abah, A.E. and B. Temple, 2015. Prevalence of malaria parasite among asymptomatic primary school children in Angiama community, Bayelsa State, Nigeria. Trop. Med. Surg., 4.

- Dawaki, S., H.M. Al-Mekhlafi, I. Ithoi, J. Ibrahim and W.M. Atroosh et al., 2016. Is Nigeria winning the battle against malaria? Prevalence, risk factors and KAP assessment among Hausa communities in Kano State. Malar. J., 15.

- Pryce, J., M. Richardson and C. Lengeler, 2018. Insecticide-treated nets for preventing malaria. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.

- Zhou, Y., W.X. Zhang, E. Tembo, M.Z. Xie and S.S. Zhang et al., 2022. Effectiveness of indoor residual spraying on malaria control: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect. Dis. Poverty, 11.

- Laurens, M.B., 2021. Novel malaria vaccines. Hum. Vaccines Immunother., 17: 4549-4552.

- Miura, K., Y. Flores-Garcia, C.A. Long and F. Zavala, 2024. Vaccines and monoclonal antibodies: New tools for malaria control. Clin. Microbiol. Rev., 37.

- Slater, H.C., X.C. Ding, S. Knudson, D.J. Bridges and H. Moonga et al., 2022. Performance and utility of more highly sensitive malaria rapid diagnostic tests. BMC Infect. Dis., 22.

- Conrad, M.D. and P.J. Rosenthal, 2019. Antimalarial drug resistance in Africa: The calm before the storm? Lancet Infect. Dis., 19: e338-e351.

- Rouamba, T., S. Nakanabo-Diallo, K. Derra, E. Rouamba and A. Kazienga et al., 2019. Socioeconomic and environmental factors associated with malaria hotspots in the Nanoro demographic surveillance area, Burkina Faso. BMC Public Health, 19.

- Patrick, S.M., M.K. Bendiane, T. Kruger, B.N. Harris and M.A. Riddin et al., 2023. Household living conditions and individual behaviours associated with malaria risk: A community-based survey in the Limpopo River Valley, 2020, South Africa. Malar. J., 22.

- Nanvyat, N., C.S. Mulambalah, Y. Barshep, J.A. Ajiji, D.A. Dakul and H.M. Tsingalia, 2018. Malaria transmission trends and its lagged association with climatic factors in the highlands of Plateau State, Nigeria. Trop. Parasitol., 8: 18-23.

- Adigun, A.B., E.N. Gajere, O. Oresanya and P. Vounatsou, 2015. Malaria risk in Nigeria: Bayesian geostatistical modelling of 2010 malaria indicator survey data. Malar. J., 14.

- Berzosa, P., A. de Lucio, M. Romay-Barja, Z. Herrador and V. González et al., 2018. Comparison of three diagnostic methods (microscopy, RDT, and PCR) for the detection of malaria parasites in representative samples from Equatorial Guinea. Malar. J., 17.

- Mbanefo, A. and N. Kumar, 2020. Evaluation of malaria diagnostic methods as a key for successful control and elimination programs. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis., 5.

- Krampa, F.D., Y. Aniweh, G.A. Awandare and P. Kanyong, 2017. Recent progress in the development of diagnostic tests for malaria. Diagnostics, 7.

- Dhorda, M., E.H. Ba, J.K. Baird, J. Barnwell and D. Bell et al., 2020. Towards harmonization of microscopy methods for malaria clinical research studies. Malar. J., 19.

- Das, D., R. Vongpromek, T. Assawariyathipat, K. Srinamon and K. Kennon et al., 2022. Field evaluation of the diagnostic performance of EasyScan GO: A digital malaria microscopy device based on machine-learning. Malar. J., 21.

- Torres, K., C.M. Bachman, C.B. Delahunt, J.A. Baldeon and F. Alava et al., 2018. Automated microscopy for routine malaria diagnosis: A field comparison on Giemsa-stained blood films in Peru. Malar. J., 17.

- Okyere, B., A. Owusu-Ofori, D. Ansong, R. Buxton and S. Benson et al., 2020. Point prevalence of asymptomatic Plasmodium infection and the comparison of microscopy, rapid diagnostic test and nested PCR for the diagnosis of asymptomatic malaria among children under 5 years in Ghana. PLoS ONE, 15.

- Hribar, L.J., M.B. Boehmler, H.L. Murray, C.A. Pruszynski and A.L. Leal, 2022. Mosquito surveillance and insecticide resistance monitoring conducted by the Florida Keys Mosquito Control District, Monroe County, Florida, USA. Insects, 13.

- Adebajo, A.C., F.G. Famuyiwa and F.A. Aliyu, 2014. Properties for sourcing Nigerian larvicidal plants. Molecules, 19: 8363-8372.

- Agyemang-Badu, S.Y., E. Awuah, S. Oduro-Kwarteng, J.Y.W. Dzamesi, N.C. Dom and G.G. Kanno, 2023. Environmental management and sanitation as a malaria vector control strategy: A qualitative cross-sectional study among stakeholders, Sunyani Municipality, Ghana. Environ. Health Insights, 17.

- Ahmed, A., K. Mulatu and B. Elfu, 2021. Prevalence of malaria and associated factors among under-five children in Sherkole refugee camp, Benishangul-Gumuz Region, Ethiopia. A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE, 16.

- Sakwe, N., J. Bigoga, J. Ngondi, B. Njeambosay and L. Esemu et al., 2019. Relationship between malaria, anaemia, nutritional and socio-economic status amongst under-ten children, in the North Region of Cameroon: A cross-sectional assessment. PLoS ONE, 14.

- Yaro, J.B., A.B. Tiono, A. Ouedraogo, B. Lambert and Z.A. Ouedraogo et al., 2022. Risk of Plasmodium falciparum infection in South-West Burkina Faso: Potential impact of expanding eligibility for seasonal malaria chemoprevention. Sci. Rep., 12.

- Ndiaye, J.L.A., Y. Ndiaye, M.S. Ba, B. Faye and M. Ndiaye et al., 2019. Seasonal malaria chemoprevention combined with community case management of malaria in children under 10 years of age, over 5 months, in South-East Senegal: A cluster-randomised trial. PLoS Med., 16.

- Rogerson, S.J., 2017. Management of malaria in pregnancy. Indian J. Med. Res., 146: 328-333.

- Gontie, G.B., H.F. Wolde and A.G. Baraki, 2020. Prevalence and associated factors of malaria among pregnant women in Sherkole District, Benishangul Gumuz Regional State, West Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis., 20.

- Oneko, M., L.C. Steinhardt, R. Yego, R.E. Wiegand and P.A. Swanson et al., 2021. Safety, immunogenicity and efficacy of PfSPZ vaccine against malaria in infants in Western Kenya: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Nat. Med., 27: 1636-1645.

- Merle, C.S., N.A. Badiane, C.D. Affoukou, S.Y. Affo and S.L. Djogbenou et al., 2023. Implementation strategies for the introduction of the RTS,S/AS01 (RTS,S) malaria vaccine in countries with areas of highly seasonal transmission: Workshop meeting report. Malar. J., 22.

- Nate, Z., A.A.S. Gill, R. Chauhan and R. Karpoormath, 2022. Recent progress in electrochemical sensors for detection and quantification of malaria. Anal. Biochem., 643.

- Kiemde, F., A. Compaore, F. Koueta, A.M. Some and B. Kabore et al., 2022. Development and evaluation of an electronic algorithm using a combination of a two-step malaria RDT and other rapid diagnostic tools for the management of febrile illness in children under 5 attending outpatient facilities in Burkina Faso. Trials, 23.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Egwu,

E.V., Hemen,

A., Eziekiel,

I., Anih,

D.C., Oko,

O., Linus,

E.N., Okorocha,

U.C., Tayo-Ladega,

O., Abubakar,

N., Clement,

U.C., Tarshi,

M.W. (2026). Comparative Analysis of Malaria Vector Sporozoite Load and Malaria Prevalence Among Vulnerable Populations in Wukari, Taraba, Nigeria. Trends in Medical Research, 21(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3923/tmr.2026.1.11

ACS Style

Egwu,

E.V.; Hemen,

A.; Eziekiel,

I.; Anih,

D.C.; Oko,

O.; Linus,

E.N.; Okorocha,

U.C.; Tayo-Ladega,

O.; Abubakar,

N.; Clement,

U.C.; Tarshi,

M.W. Comparative Analysis of Malaria Vector Sporozoite Load and Malaria Prevalence Among Vulnerable Populations in Wukari, Taraba, Nigeria. Trends Med. Res 2026, 21, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3923/tmr.2026.1.11

AMA Style

Egwu

EV, Hemen

A, Eziekiel

I, Anih

DC, Oko

O, Linus

EN, Okorocha

UC, Tayo-Ladega

O, Abubakar

N, Clement

UC, Tarshi

MW. Comparative Analysis of Malaria Vector Sporozoite Load and Malaria Prevalence Among Vulnerable Populations in Wukari, Taraba, Nigeria. Trends in Medical Research. 2026; 21(1): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3923/tmr.2026.1.11

Chicago/Turabian Style

Egwu, Elu, Victoria, Agere Hemen, Iliya Eziekiel, David Chinonso Anih, Okechukwu Oko, Emmanuel Ndirmbula Linus, Ugochukwu Cyrilgentle Okorocha, Oluwadamisi Tayo-Ladega, Nusa Abubakar, Uguru Chukwudi Clement, and Monday William Tarshi.

2026. "Comparative Analysis of Malaria Vector Sporozoite Load and Malaria Prevalence Among Vulnerable Populations in Wukari, Taraba, Nigeria" Trends in Medical Research 21, no. 1: 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3923/tmr.2026.1.11

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.